The crowd on July 11, 2023, was larger than usual for city council hearings. Bountiful City Manager Gary Hill got up to give a presentation on the city’s deal with UTOPIA Fiber, noting that the potential of contracting with the public-owned broadband agency had drawn significant interest. “It’s not often we have a mostly full room,” Councilman Jesse Bell said as he introduced Hill.

Several weeks earlier, on May 26, the city council had unanimously passed a plan to install fiber internet in residential areas. Problems followed when a group called the Utah Taxpayers Association (UTA) began gathering signatures to drop the plan.

Bountiful went into damage control mode. In July, American Association for Public Broadband Executive Director Gigi Sohn penned an op-ed in the Salt Lake Tribune advocating for Bountiful’s plan to be implemented. Trade publications focused on public-owned broadband picked up the news and talked about how a dark money organization was funding “anti-competition” programs in Bountiful.

By summer, the deal went through despite the petition-gathering campaign. It was a unique moment because Bountiful decided to create its own utility, unlike most of the previous build-outs of the agency’s tech. UTOPIA will build the fiber connectivity in the coming years, and the city will own the infrastructure.

“They’re a public power city. They did a lot of surveys and said that one of the key things that their residents like is the ownership of what Bountiful has provided for them,” UTOPIA’s CMO Kim McKinley says, noting that UTOPIA doesn’t actually provide the internet itself but instead builds the infrastructure and then allows private internet companies to use it, ensuring they can create the best possible access without threatening internet service providers (ISPs).

To illustrate this, she likens UTOPIA to an airport: Salt Lake City builds the airport, and then Delta, Southwest, and other airlines have the option to fly in and out of it. According to the company, UTOPIA is the nation’s largest and most successful community-owned open-access fiber network and offers the nation’s fastest internet speeds, up to 10 gigabits per second for residents and 100 gigabits per second for businesses. For the last 15 years, every UTOPIA project has been paid for completely through subscriber revenue.

But that’s not what those leading the campaign against UTOPIA would have internet customers believe.

The campaign against UTOPIA Fiber

By November 2023, a new organization was targeting UTOPIA by running television ads against the agency and sending anti-UTOPIA mailers to project areas.

“Government-run networks mean waste, corruption and failure,” declared an ad campaign that played across Utah in late 2023, paid for by a group called NoGovInternet.com, a project of the Domestic Policy Caucus.

“We were seeing TV ads first, and now we’re seeing a very aggressive attack campaign that is hitting cities throughout the state—both cities that have been working with us and potential cities,” said UTOPIA Executive Director and CEO Roger Timmerman at a Wednesday press conference in Murray, Utah. “Overwhelmingly, our customers in these communities are very quick to identify that this information is misleading and inaccurate. … We don’t even know who is behind the campaign and can’t get them to respond to correct the information. We believe this is probably an effort from incumbents who don’t want competition.”

Timmerman claims UTOPIA hasn’t been negatively impacted by the attack ads and instead enjoyed the best year it’s ever had in 2023. In December, UTOPIA announced the successful completion of its build in the city of Santa Clara, Utah, its fifth city in 2023 and 19th city overall. A company press release claims UTOPIA Fiber has expanded its subscriber base to over 60,000, serving approximately 200,000 businesses and homes across more than 50 communities in Utah and the West.

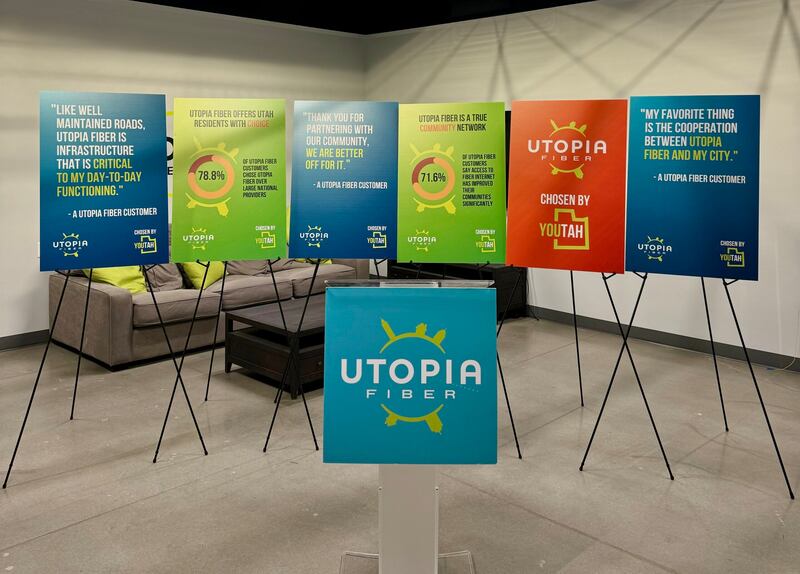

In response to the campaign against UTOPIA, the company unveiled its own campaign at the press conference on Wednesday. The “Chosen by YOUtah” campaign serves to highlight the role Utah residents have played in founding UTOPIA Fiber and shaping the network’s future.

“It’s amazing that, in Utah, we have access to the largest open-access, community-driven fiber broadband in the country,” UTOPIA Fiber Director of Government Relations Nicole Cottle said during the press conference. “Some of the benefits it has brought to our state are increased competition and the increasing of broadband availability. … There are many things that make Utah great, and this happens to be one of them.”

The history of UTOPIA Fiber

UTOPIA’s approach focuses on individual communities and has grown as more communities in Utah request access. It all began in 2002 when 11 cities from the state decided to join forces and create an agency that would build faster internet in their area.

“Back in the early days, the cities went to the major telecom incumbents of the area—the cities who started this project—and said, ‘We would like for you guys to build in our area. We see that the internet connectivity is going to be important for our cities as we go forward,’” McKinley recounts of UTOPIA’s origin. “And at that time, those incumbents just elected not to build in those areas. … These cities took it upon themselves in a very ‘Utah spirit’ way to say, ‘Well, if they’re not going to deliver, we’re going to figure this out [on our own].’”

At the time, the focus wasn’t fiber internet because the technology hadn’t been developed yet. McKinley notes there were many legislative challenges for the agency to overcome before it could figure out a more effective structure.

“The reason people partner with us is because we’ve done everything wrong,” she says. “We’ve gone through the trenches. We want to help lift other networks until they’re at a point where they can operationally break even, and then they can go and do it on their own.”

By 2010, UTOPIA created a subdivision called UIA, which focuses more on growing the agency and working with communities that want to join the network. The agency has a board made up of the original cities that created it. When they build in an area, cities take out bonds so that it isn’t paid by taxes but rather through subscriber fees. Individuals pay a flat rate to UTOPIA each month plus a rate to whichever ISP they pick to actually provide their internet. The revenue UTOPIA earns from subscriber fees goes back to continuing to build the network, and there’s a board that oversees where it goes, according to McKinley.

Power for the people

One of the success stories McKinley points to is how UTOPIA installed internet for Morgan, Utah. As the pandemic proved internet access to be absolutely crucial for everything from education to health care delivery and daily work routines, rural communities are often left behind across the nation. Municipal broadband agencies have routinely tried to center those concerns in their platforms to build accessible connectivity.

The town of less than 5,000 in the state’s northern center wouldn’t have been an obvious priority under normal circumstances for UTOPIA, given its size and accessibility. But the city was able to trade, McKinley says, instead of taking out bonds to build the project.

“The reason we were able to get to rural Morgan, Utah, is because we did a UDOT trade,” she says. “They had some conduit and some stuff going up there, so we just did a trade: ‘If you give us this, we’ll help you somewhere else that you need assistance.’ And so if you do those little co-operations and talk to people and see what’s possible, I think those things can happen.”

McKinley notes that where private companies don’t have the incentive to get fast and effective internet everywhere—especially lower income areas or logistically challenging places—public utilities can figure out solutions with the cities and through subsidies plus through not having to generate large revenue.

For McKinley, the problem with attack ads is less about UTOPIA and more about an existential issue for private companies. She notes that being an open-access platform allows the ISPs a benefit: not having to pay to build the infrastructure but getting to benefit from it by signing new clients.

She believes the fight from private companies has more to do with opposition to a normalization of municipal ownership, which might lead some public utilities to eliminate private internet providers altogether. But in her mind, UTOPIA belongs in government.

“We view this very much as an infrastructure play more than anything,” she says. “It’s not just important for YouTube; it’s important for smart city apps, it’s important for monitoring, it’s important for everything coming down the line. I think what they’re really scared of is what could be if a visionary comes in and changes something.”