This story appears in the April issue of Utah Business. Subscribe here.

The first practical application of robotics made its debut in Detroit in the early ’60s when the Unimate robotic arm joined the production line at a General Motors plant. A crude machine by today’s standards, perhaps, but one capable of tirelessly lifting and stacking the heavy die-cast steel components of the day.

The auto manufacturing industry has gone on to embrace the technology at ever higher scales. A typical assembly line now looks more like futurescapes wrought by science fiction authors than the original “moving assembly line” that Henry Ford deployed in the early 20th century, albeit one that could produce a completed Model T every 90 minutes.

Robotics have since burgeoned far beyond the manufacturing floors of automakers, now numbering in the millions globally and increasingly deployed in a wide range of processes. Marina Bill, president of the International Federation of Robotics, noted in a recent report that robot “density” hit an all-time high of 151 robots per 10,000 workers in 2022, more than doubling the figure of just six years ago. In the United States, the ratio is even higher, with 285 robots per 10,000 employees and a robot density ranking 10th in the world.

Along with the proliferation of ever more advanced robotics and manufacturing automation have come fears that the innovations will replace human workers. Fast-advancing artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning tools, the “brains” that drive many robotic processes, have only fanned the flames of those concerns. In an interview last year, Microsoft founder Bill Gates predicted that AI-powered humanoid robots were on track to become more affordable than human laborers and will begin replacing blue-collar workers.

Alongside those concerns are the track records of companies for which robotics and automation form the very core — and whose successes and growing employee ranks would not exist but for advanced innovations.

Higher quality, lower cost

Utah’s Ultradent Products, Inc., started in the late ’70s when founder and dentist Dr. Dan Fischer innovated a product that helped control bleeding during dental procedures. Fischer hoped to sell his idea to an established medical device manufacturer, but after he was unable to find a taker, he decided to launch his own company.

Ultradent is now a global leader in specialty products and devices for the dental industry, with a product portfolio numbering over 1,600. According to its leaders, the company’s embrace of robotics and automation has been an essential driver of its success.

Peter Allred, Ultradent’s SVP of Manufacturing and Supply Chain, says the privately-held company leaned on growth financing to phase in robotics and automated processes beginning in the ’90s. The transition, he noted, was one borne of the quest for elevating quality and consistency over mere cost reduction.

“We started with processes that were prone to human-caused quality variation and operations that required high dexterity, repetitive or tiring motions,” Allred says. “Today, all of our device manufacturing of more than 1,600 products is at least partially automated, and dozens are fully automated up to final packaging, which is still performed manually. … I would say, generally speaking, we have not ever really used automation as a means to drive cost savings, though that is certainly a side benefit. It’s really been more focused on taking away labor requirements where we know human interaction will affect quality.”

Allred says Ultradent’s impetus to innovate has drawn inspiration from those who have “approached the world with curiosity” and dreamt up ways to contribute to it, citing Ford, the Wright brothers, Leonardo DaVinci, famous Toyota engineer Taiichi Ohno and others.

While inspired by the historic work of industry titans, Allred says Ultradent has taken a holistic approach to adopting and integrating robotics and automation, paying particularly close attention to wider impacts and outcomes.

“It is easy to miss much of the value of automation if we don’t carefully consider how it fits into the overall production system,” he says.

Among those chief concerns are impacts on Ultradent employees. Ultradent’s robotics and automation systems have helped replace manual manufacturing processes heavy on repetitive motion — the kind of jobs where workers can be plagued by ergonomic injuries that come with that level of repetition, Allred says.

By integrating the new systems alongside employees rather than replacing them, Ultradent’s technology adoption has had transformational impacts on its employees. Not only have they stayed on, but they have also been upskilled along the way, leading to higher wages for those workers.

It’s an approach that has resonated with Ultradent employees.

“I would wager that there isn’t a single employee who, if you asked them about our strategy with respect to automation, ever believed it was a threat to their employment,” Allred says. “Over, say, 25 years … we have not seen a net decrease or layoffs associated with the integration of robotics or automation.”

Mind x machine

While Ultradent’s business journey of 45-plus years has relied heavily on the adoption and integration of robotics and automation, Salt Lake City-based biotech firm Recursion Pharmaceuticals sprang to life with a model intrinsically connected to the technology.

Recursion was founded in 2013, and its innovative approach began as the core of doctoral research performed by company co-founder and CEO Chris Gibson at the University of Utah. The original innovation relied on automating the once human-intensive process of peering through a microscope to assess if a chemical compound’s impact on a diseased cell is positive or advancing it toward being a healthy cell. The technique involved taking a sample cell representing a genetic disorder and testing it against the effects of hundreds of thousands of chemical compounds in a process that automates the visual evaluations and data gathering to allow for a lot of testing in a very short period.

Recursion has since broadened its drug discovery operations with systems that facilitate unprecedented volume of procedures. Robotics and automation help drive over 2 million “mini-experiments” every week, according to Recursion VP of Product Lina Nilsson.

This technology has been a primary driver of Recursion’s stellar growth from a handful of scientists operating out of a lab at the University of Utah Research Park to its current employee count numbering north of 500, two expansive facilities at The Gateway and multiple international satellite operations.

Recursion’s business development arc has also spawned a novel employee demographic, one that may very well represent the future of high-tech operations in the biotechnology space and beyond.

Nilsson says Recursion has built its talent pool in a way that is integrated with its technological advances in a thoughtful design process that brings engineers, software specialists and scientists together in a daily collaborative process.

“We may represent the new era of biotechnology companies,” Nilsson says. “[Recursion talent is] split between people with technical expertise and scientists. Many companies are skewed to one side or the other, but that’s not how we have built our teams.”

Nilsson says when and where robotics and automation are utilized in Recursion’s work is a matter of utility, and much like Ultradent, the company is on the lookout for areas where it can find efficiencies and reduce the variations inherent to manual processes.

“At a fundamental level, we don’t just start with a cool piece of automation,” Nilsson says. “We’re identifying the opportunities for step-function improvements. What are the biggest points of toil we can remove?”

Nilsson says the strategy allows for making the best and highest use of its in-house expertise.

“If I go back and think about how we did things even a year or two ago, having groups of employees searching the internet for data or doing manual quality control checks, we’ve made significant progress,” Nilsson says. “The improved efficiencies allow our amazing scientists to spend their time on the really meaningful problems.”

While Recursion continues to build out its robotics and automation processes, Nilsson says there is an ongoing, concurrent effort to identify the best nexus points for human interaction.

“We work at being really thoughtful about the right moments to have humans in the loop and where the inflection points are,” Nilsson says. “We don’t want people doing a thousand tasks. We look at it as a virtuous cycle of interactions between humans, automation and our machine learning processes … with humans as the catalyst for improvement.”

Reality check

Brigham Young University professor Marc Killpack studies human-robot interactions and notes that while the evolution of robotics technology is one moving at lightning speed, a wholesale displacement of human workers — à la Gates’ gloomy prediction of humanoid labor bots — is still a good way off.

Killpack says purpose-built, specialized robotics are a much easier lift from a technology development standpoint, noting the difference between current technology — which can, for example, vacuum a house or mow a lawn on its own versus a robot pushing around a vacuum or lawnmower.

“Observing and reasoning about the world is quite different than interacting with it,” Killpack says. “AI platforms have evolved to a high proficiency in looking at a scene and telling you everything that is going on, but developing a robot that can interact with that scene involves a lot of physics, and the mapping between action and activity with perception is highly complex. … I think we’re still pretty far from that happening at anything near a human-replacement level.”

But even at the level of non-humanoid, task-specific robotics, Killpack says a lot of thought is required to optimize automation for the still-necessary human interactions that accompany it.

“You can design something amazing, but people have to be able to work with it, or you don’t get the benefits,” Killpack says.

A balancing act

Conducive and productive interaction between workers and robotics systems are very much on the minds of leaders at both Ultradent and Recursion.

Nilsson notes that many newly graduated scientists, as well as those moving to Recursion from other companies, are joining the team with at least some exposure to and experience with robotics and automation as the technology becomes more widely accessible.

“There’s a convergence of new tools and technologies,” Nilsson says. “We’re beginning to get people who have some of that cross-training and experience. It was a much different situation a decade ago.”

Recursion also offers ongoing training opportunities for its employees as it continues to ramp up and expand its technology, part of a structure that cultivates and maintains the human-technology symbiosis at the heart of the company’s success.

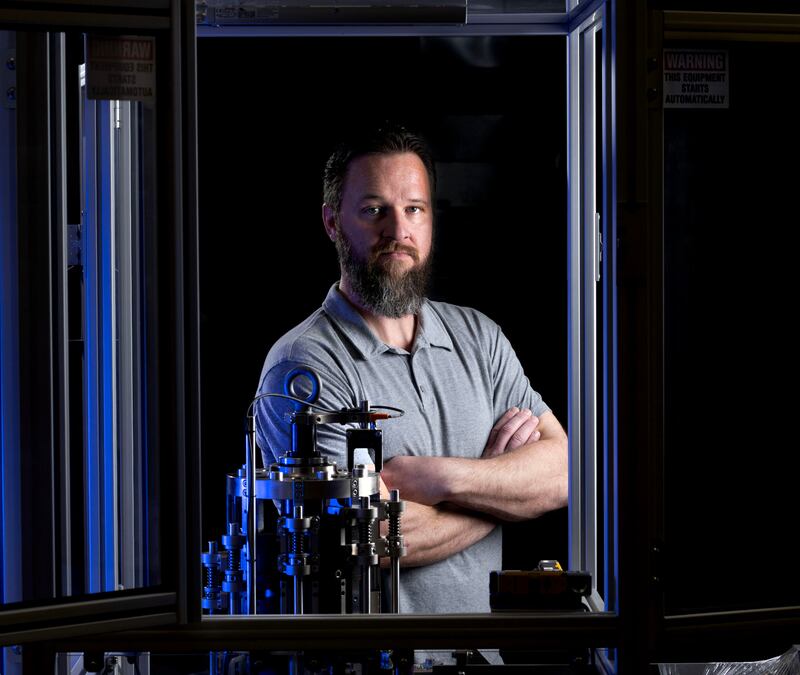

In many instances, Ultradent’s specialized product category has compelled the company to develop its own robotics and automation devices in a process that Allred says bears both challenges and benefits.

On the plus side, the company’s proprietary builds allow it to finely tune its integration of technology in its human-dependent manufacturing processes. It also requires Ultradent to maintain a broad range of on-staff skill sets.

“The biggest challenge is to develop and maintain expertise in the many different areas of knowledge we need to make an automation project successful,” Allred says. “That includes technical subjects within mechanical, electrical and controls engineering. It also includes execution-based skills like project management and soft skills like communication and team building.”

In the end, those strategic technological accomplishments in robotics and automation have paired with — and fueled — an ever larger, higher skilled and higher paid employee group that’s tracked with Ultradent’s ongoing success.