Utah’s educational professionals encourage others to become teachers

Think back to your favorite teacher. We all have at least one. Mine was Mrs. Collier. She taught AP U.S. History while singing, dancing around the room and narrating vivid stories. She loved unconditionally and saw limitless potential in her students. I still remember some of the history, but most importantly, I remember what she taught me about the power of being myself and making a difference in my corner of the world.

Sydnee Dickson, the state superintendent of public instruction for the Utah State Board of Education, feels the same way about her teachers. Dickson’s grandma was her first teacher in elementary school. “Watching what she did really set me on a path of wanting to be a lifelong learner,” Dickson says. “Learning is fun and exciting to me because of the way I started out in school.”

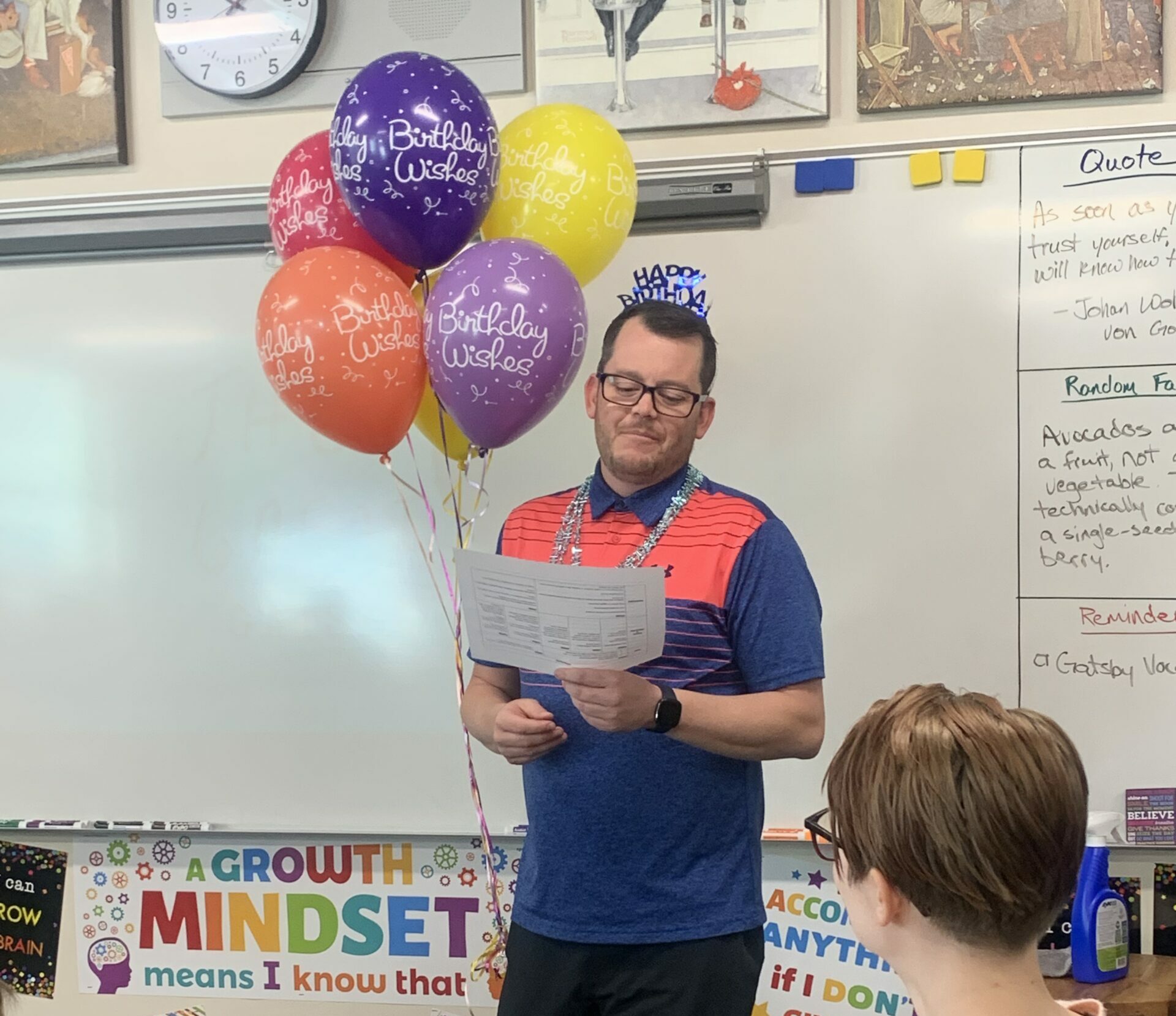

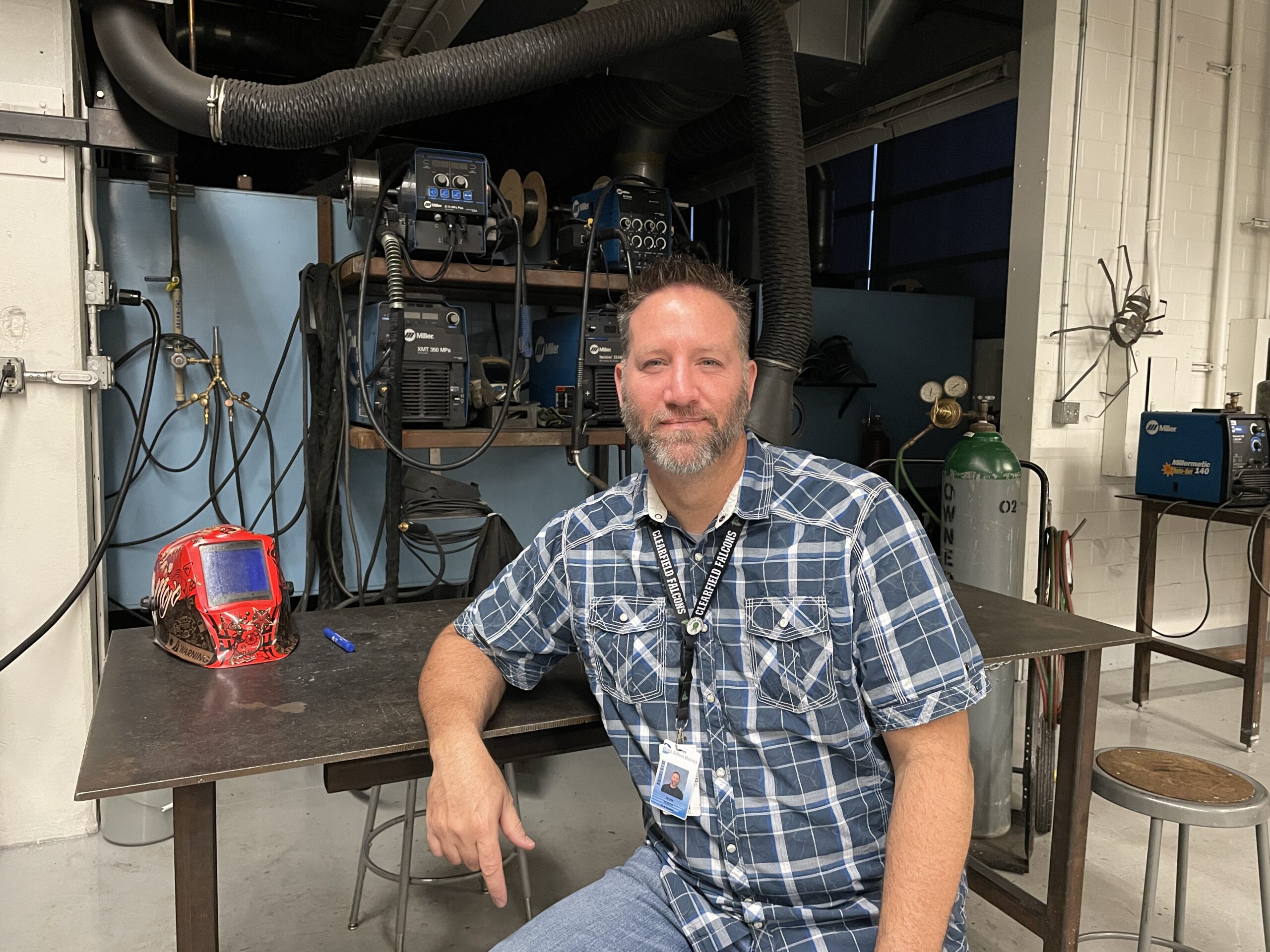

For some, that inspiration is the motivation for becoming a teacher. “We all have had a teacher that affected our lives,” says Devin Rusch, a beloved welding instructor at Clearfield High School. “We want to do the same thing for other people.”

Beware the “implementation dip”

While an inspirational profession, teaching infamously comes with its hardships. “The first years of teaching are extremely difficult,” Dickson says.

Rusch taught every other day while still welding at night during his first year as a teacher. On the days he didn’t teach, Rusch would get off his welding job at 2 a.m., head to the school and work on remodeling the shop so it would be fit for students to work in.

Ryan Rarick, an education pathway teacher at Career Tech High School, was similarly busy at the start of his career: coaching the basketball and volleyball teams, teaching AP classes and building up the concurrent enrollment program. “To be totally honest, I burned myself out,” he says.

Currently working on his Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction, Rarick discusses the “implementation dip” many new teachers face. The researched phenomenon happens when people start something new, only to face the harsh reality of being worse at their new endeavor than at whatever they did before. “That’s what a lot of new teachers face,” Rarick says.

But Dickson says, “When you face something hard, it’s always coupled with lessons learned and silver linings.” Those lessons build better teachers. “You may not see it day to day, but there is a ripple effect you’re having on your whole community,” agrees Tabitha Pacheco, the director of education programs at Hope Street Group and a special education public information officer for the Utah State Board of Education.

Luckily, new teachers aren’t alone. Utah has structures to encourage and develop new teachers—such as mentorship programs. “Having a mentor … is paramount to making sure that we can retain our young teachers,” Dickson says.

Rarick’s mentors helped him overcome the implementation dip and gain confidence in his skills. “I just felt a ton of confidence in myself and had good feedback from my instructional coaches,” he says.

Inspired by his coaches’ support, Rarick spent a couple of years mentoring others and passing along the support he was given. He often focused on helping fellow educators “sift through all the things they have to think about, identify the most crucial things, get good at those and set and reach goals.”

Passionate about supporting teachers, Pacheco, who also helped found the Utah Teacher Fellows program, explains, “My whole job is elevating the profession!” After teaching in special education programs for 10 years, Pacheco became a national teacher fellow. While still teaching in her own classroom, the role had her traveling across the nation to meet with other teachers about education challenges, visit other states’ departments of education, learn more about the national teaching landscape and bring her findings back to Utah. After her fellowship ended, Pacheco worked with Dickson to create the Utah Teacher Fellows program to train teachers to be leaders in their communities.

That support makes a difference. “The challenge stays the same,” Rarick says, but with time and assistance, “your ability to teach gets better. You gain perspective on the crucial things.”

Perks and places for change

Still, education is not a perfect system. “It’s really easy to point out issues in education,” Pacheco says. “But if you’re just complaining, you’re not making a difference.” Pacheco’s years as a teacher fellow were “a big shift” in her career as she got to see things from “a much broader lens” and felt empowered to change things.

Rarick had a similar experience when he discovered that a disproportionately small percentage of students of color were enrolled in his school’s honors, AP and CE courses. Instead of sitting back and lamenting the education system’s failures, Rarick gathered student recommendations from teachers of younger grades, wrote personal invitations to the advanced courses, and involved the assistant principal in meetings with students. The representation percentage rose in those courses and continues increasing even though Rarick moved to another school. “I saw that change the way that students thought about themselves,” Rarick says.

He is now working on a similar project to improve representation percentages among teachers by recruiting students of color into his school’s education pathway—a program designed to inspire and prepare students to become teachers.

There are problems in education, but teachers are not helpless byproducts of a failed system. They are agents of change. “Schools are the hearts of our communities, and teachers are the leaders,” Pacheco says.

Along with the ability to encourage and enact true change, teaching has many other perks. Likely the most well-known bonus—teachers get all holidays off, not to mention seasonal breaks.

In addition to that, teacher salaries in Utah have recently risen significantly. In 2023, Utah legislators approved an annual $4,200 pay raise for licensed educators, with an additional $1,800 in benefits, and educator salary adjustments based on weighted pupil unit growth. Some Utah school districts are even paying first-year, licensed teachers over $60,000.

Teaching jobs also provide stability and security, even during pandemics and recessions. “The pandemic … was probably the most challenging era of education in several decades,” Rarick admits. “But I did not have to stress about whether my job would still exist post-pandemic or if I would get laid off and not have an income source.” In fact, all Utah public school teachers have pension coverage, a benefit almost unheard of in today’s economy.

And the opportunities for career growth and leadership as a teacher are endless. “Sometimes you get that mentality of, ‘Oh, I’m just a teacher,’” Pacheco says. “But I think teachers can do anything!” In her education career alone, Pacheco has developed tangible skills in technology, communication, leadership, project management, nonprofit organization, grant writing, budgeting, legislation and more.

“That’s the role of a teacher: to help young people see the possibilities for themselves and give them the tools to be able to succeed in achieving their goals and dreams.”

Become a teacher now, during or even after your career

For those who are drawn to teaching but don’t want to sacrifice time away from their careers to go back to school, there are alternate routes to becoming a teacher. Utah allows individuals employed in approved Utah school districts or charter schools to enroll in an Educator Preparation Program designed to help people get their teaching licenses.

Rusch followed a similar path when he started teaching at Roy High School. He taught welding under a provisional license so he could get an immediate start as a teacher while simultaneously earning his official teaching license. Teachers from that path offer students a much-needed perspective from the professional world.

“If schools don’t have professionals teaching these kids, I don’t know how else they’re going to get that knowledge. Without industry professionals in schools, the world would really struggle,” Rusch says.

There is also the option of becoming a paraeducator, which only requires obtaining an associate degree and passing an exam. “There is such a need for paraeducators in our schools, and this is a great way to work with students and make a difference in the community,” Pacheco says.

In a world where YouTube and AI educate 24/7, some would argue that the need for teachers is becoming obsolete. But there is a nuanced aspect of education that no robot could replace. “These kids have all the information available at their fingertips,” Rusch says. “But teachers give kids a chance to see how they can apply that information.”

Beyond the necessary human touch in actual learning, teachers build emotional fortitude in students. “The ability to love and value students can’t be replaced by artificial intelligence,” Pacheco says. Dickson reflects on moments of “holding [kids] together” when they were facing difficult situations. “The kids need us,” Rusch says. “A lot of kids come from broken homes, and they need a source of stability in their lives. I don’t just care for them as students; I care for them for the rest of their lives.”

Rarick depicts teachers as the threshold guardians in the “hero’s journey” archetype, the ones who stand guard at the border of the known and the unknown. “Teachers get to be that for students,” Rarick says. “We open the gate and push them through when they’re ready. We are advocates, and students carry that with them into their lives.” Without those guardians, students would never be able to glimpse the level of potential that can only come from stepping into the unknown.

“My goal in life is to build capacity in others,” Dickson says. “That’s the role of a teacher: to help young people see the possibilities for themselves and give them the tools to be able to succeed in achieving their goals and dreams.”

The value and impact of a profession like no other

Not only do teachers impact students, but students also have a significant impact on teachers. For Pacheco, running into one of her former special education students in a grocery store was “a really rewarding moment” as she got to see them as a “successful, happy and thriving” adult. Rarick laughs when former students still send him memes inspired by “The Great Gatsby,” a book he shared with his English classes, years after the fact. Rusch loves hearing from students who reach out long after leaving his class to tell him about finding a great welding job and to thank him for giving them a start.

But the rewards of teaching don’t always come so far down the road. “When I walk the halls and kids yell out to me, ‘Hey Rusch!’ that’s the best part for me—knowing that I’ve had an impact on these kids. It’s fun to be part of these kids’ lives because I want them to be the best they can be, and I want the kids to know that,” Rusch says.

“When we value teachers, we get better outcomes for our students. And that takes all of us,” Dickson says. “As a state and as communities, when we lean in to do everything we can to support our teachers, we impact generations of kiddos.” For some, that will mean becoming teachers and committing to push through the implementation dip. Utah is currently losing 45-50 percent of educators in their first five years of teaching. Dickson is working to combat that loss by advocating for supportive leadership, good working conditions and pay, and a positive school culture and climate. But she can’t do that alone.

Current teachers, potential teachers and community members can take action by finding other people who are “solutions oriented,” Pacheco says. “Be involved in what’s happening. Know who is representing you. Go to the school board meetings. Vote for people to represent you who you think will do what’s best for your student and your family values,” Pacheco urges.

After all, our Utah teachers are worth it. “Every day, I am inspired by the teachers I work with, almost to tears,” Pacheco says. “They should all be teacher of the year. They are exceptional. If people have questions about Utah education, they should go visit our schools. They will see some really amazing things happening.” ![]()